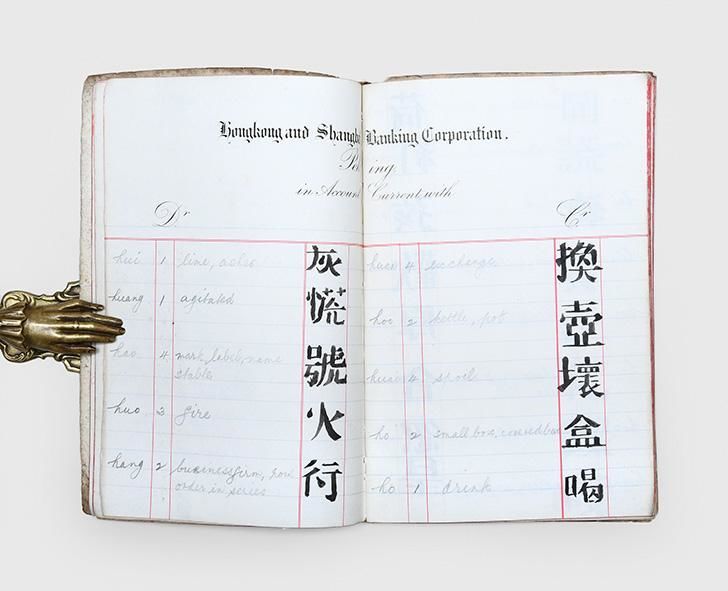

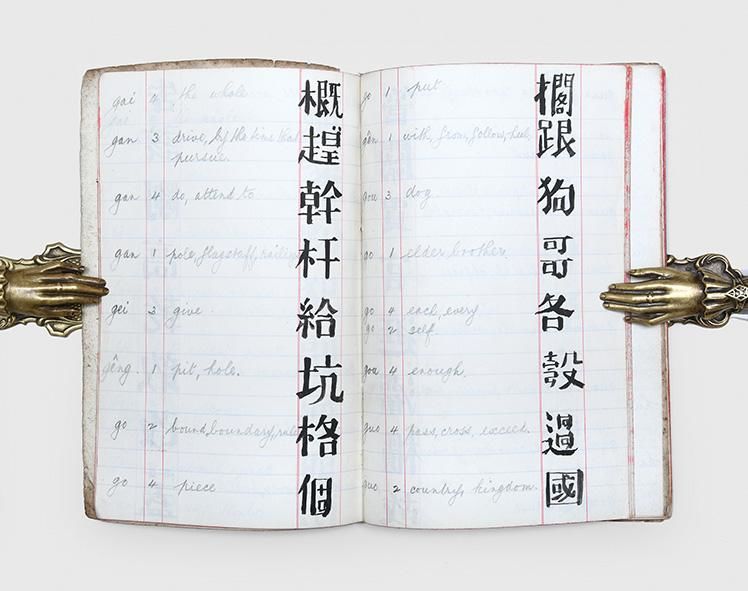

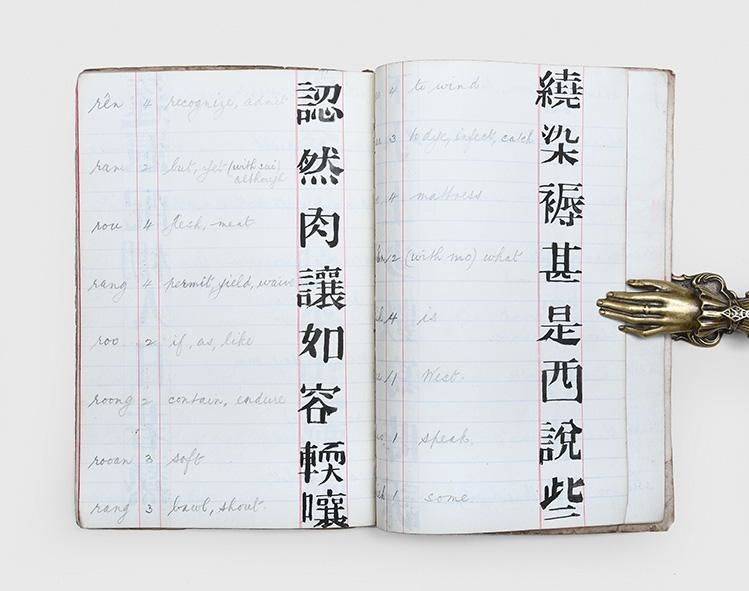

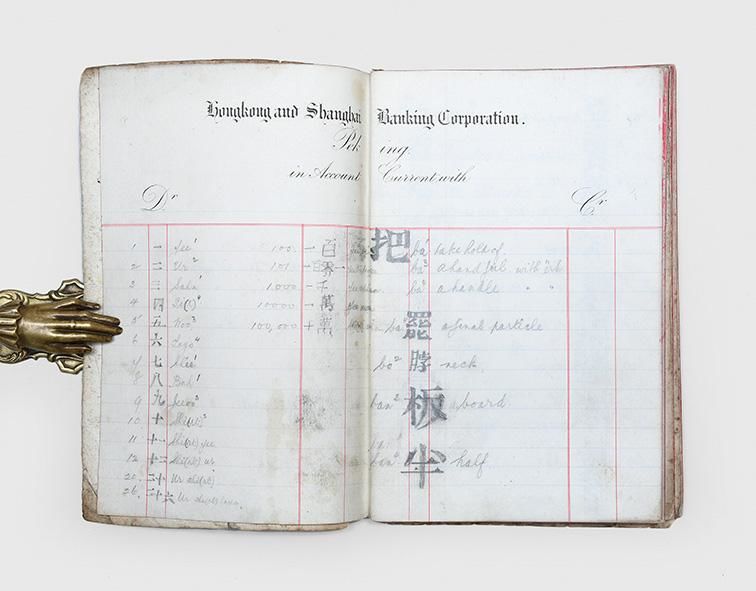

[Likely Beijing: , c.1900]. Language learning at China's premier banking institution A connection to the late Qing dynasty and the Legation Era: a banker's vocabulary list for learning spoken and written Chinese, produced during the tenure of HSBC's legendary Peking agent Edward "Guy" Hillier, when political upheavals brought new diplomatic stresses and economic opportunities for China's largest foreign bank. The ledgers from which this example is formed were only produced between 1890 and 1910. HSBC entered the China market in Hong Kong in 1865 and, because Chinese reformers began to look for more foreign investment in government projects, it established a Peking office in the Legation Quarter in the 1880s. Quickly, Guy Hillier (1857-1924) was drafted to lead operations. Fluent in Chinese, Hillier was the bank's chief representative in the Chinese capital from 1891 to 1924, although he managed to avoid be out of the city during the Boxer Uprising. "Hillier tested the very limits of the 'treaty system', establishing close relations both with modernizing compradores and with imperial officials. It was Hillier's genius to understand the politics of the foreign diplomatic community, to learn what was possible in the London market, to determine what was acceptable politically in China, and to match all threeon terms to the benefit of the Hongkong Bank, its associate companies, and, indeed, the general British position in China" (ODNB). Hillier needed well-trained, multilingual staff to handle HSBC's growing involvement in loan negotiations. This manual, containing over 1,000 entries, suits this purpose, combining English words with their Chinese character equivalents and a romanized form (with tone numbers) for pronunciation purposes. Fittingly for a banker, it begins with numbers from 1 to 100,000 and their simple logic (the number "20", for example, being formed from the characters "2" and "10"). The contents is then arranged alphabetically by romanization and ranges from the essential ("you" and "quick") to the complex ("camel" and "deaf"). The final two pages contain a list of common fruits and vegetables in English and romanized Chinese. The regular, stiff form of the Chinese characters, as well as the inclusion of serifs on strokes, echoes the songti fonts found in many contemporary western works on China and suggests that the writer was a learner copying directly and cautiously from a printed dictionary, rather than an experienced linguist producing the manual for a colleague. Several leaves see the learner tackle the complexities of words and sentences formed from multiple characters. "Bicycle", for example, is explained as the combination of the Chinese characters for "self", "proceed", and "carriage", while "woo yuan woo koo dee" is given for the phrase "without cause of reason". Over the page, they pair such phrases such as as "I tomorrow give you money" and "Have fish fresh not have" with their romanization, indicative of attempts to get to grips with the logical distinctions between Chinese and English syntax. Also given is a list of countries with their Chinese pronunciations - with the exception of America, Russia, and Japan, these are all European nations. The compiler's identity remains unknown. Fourteen individuals worked in HSBC's Peking office under Hillier between 1895 and 1908. This manuscript bears all the hallmarks of one of these bankers cutting their linguistic teeth in the complex atmosphere of late-imperial Peking. Octavo (210 x 133 mm), ff. [72]. Contemporary buff card wrappers, 132 pages filled in ink and pencil. Formed from 3 ledgers, each with red edges and and 12 bifolia ruled in red on recto, the opening bifolium of each ledger with Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Peking letterhead printed in black, all bound into wrappers with cord. Binding sturdy, staining and soiling to wrappers and contents, 40 mm closed tear slightly intruding into manuscript on one page: a very good example.