ABA News

National Book Collecting Prize Winners: Hannah Swan - Swizzle and Serve

An interview with the 2022 National Book Collecting Prize joint-winner Hannah Swan.

Congratulations again on winning the 2022 National Book Collecting Prize. How did you find out about the Prize?

I was aware of the prize for a few years, having won the David Laing Student Book Collecting Prize while completing my master’s at the University of Edinburgh in 2018. I didn’t end up putting myself forward for the National Prize that year, but decided to go ahead and throw my hat in the ring after winning the Anthony Davis Book Collecting Prize this past year.

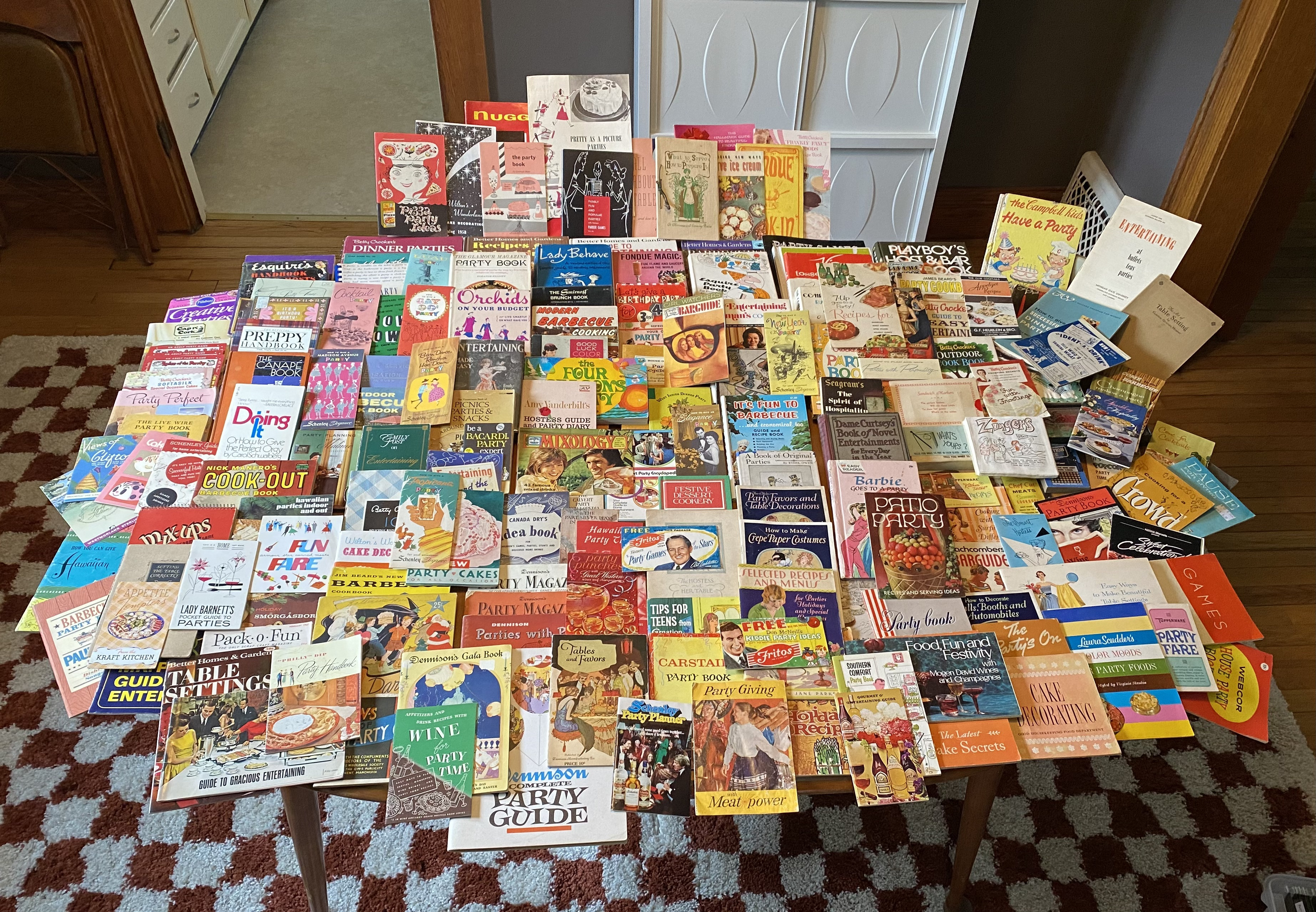

Your collection, ‘Swizzle and Serve: Party Planning Books and Ephemera, 1950-1970’ is unusual and charming! What drew you to this area of collecting?

I have been interested in the midcentury period since high school and began by collecting cookery books and ephemera from the 1950s and 1960s. I have always loved the off-the-wall flavor combinations and the showmanship of that era of cooking—much of my early collecting was purely for the hilarity of how gross the foods were!

While studying on the MSc program in Book History and Material Culture at the University of Edinburgh, I wrote my master’s dissertation on party planning books published by men’s and women’s magazines, specifically Playboy and Cosmopolitan. I was interested in how sexuality, gender, and class influenced the bibliographic design and paratexts of the books. I already had party planning texts in my collection, but began to seriously collect around parties around this time, in part to have source texts from which to draw.

My dissertation research underscored to me that these materials were not held in any meaningful number by most libraries and that no one else seemed to be collecting them. They are such important records of social history broadly and women’s history specifically (while also being incredibly visually appealing), I felt almost an obligation to preserve them! Since then, my collection has grown to approximately 186 pieces of ephemera and fifty books related to party planning in America in the twentieth century.

What is your absolute favourite item from the collection?

This is such a hard question—it’s like picking a favorite child! Some items I love for their uniqueness; some have sentimental value—especially those passed down to me by female relatives or given to me as gifts; some actually have great ideas that I have used for planning my own parties; and some are hilarious for the absurdity of the suggestions!

I’m always seeking out unique material types, so one of my favorite items is the LP of “Hear How to Plan the Perfect Dinner Party,” an audio party planning text written by Dorothy and Gaynor Maddox and published by Curtis Publishing Company in 1959. Gaynor Maddox was a nationally syndicated food writer and editor who also wrote a handful of cookbooks. His wife Dorothy also wrote food columns, though was not as widely published. It’s also an exceedingly rare item, only held by two libraries globally according to WorldCat. Other favorite unusual materials include cocktail napkins, “Ident-a-Drink” name tag stickers for drinks, needlebooks, and various paper-based party games.

I have a deep love of tablescapes—to me, the design and laying of the table for the visual pleasure of one’s guests gives a really interesting historical perspective on taste (in all its literal and figurative iterations). Plus, of all the tips, tricks, hints, and helps, the table setting suggestions are those I turn to most often in my own party-throwing. I have carved pineapples into rafts of piña coladas, sculpted quivering towers of Jell-O, spent hours at the thrift store sifting through dishware to find the perfect vessel for my garnishes—all in the name of the table!

Some of my all-time favorites have to be the booklets written by Nancy Prentiss, who styled advertisements for the Westmorland Silver Company. I had been searching for one in particular, “The Perfect Hostess”, for several years, only to come across a near-fine copy in an antique mall in rural South Dakota. I am only slightly embarrassed to say that I audibly gasped and did an excited little hop upon seeing the distinctive bright purple cover! More recently, while in London for Firsts this May, I also visited the PBFA’s London International Book Fair, where I picked up an incredible plate from an unnamed nineteenth-century book. It illustrates an “Artistic Arrangement for Dinner Table,” featuring a decorative pond (!!) for the table centerpiece, complete with tiny Venetian gondolas and sculptural mermaid fountain.

Finally, I love to see the small pieces of evidence the female readers left on these party-planning texts. Splatters of grease on a page dedicated to making donuts, manuscript adjustments to recipes, a shopping list and receipts pinned into the back of a Depression-era little cookbook, or, a personal favorite, table diagrams and measurements sketched out in pencil on the back of “The Hostess and Her Table” (a 1927 booklet advertising Tiffin glassware), all give material trace to the ephemeral act of cooking, hostessing, throwing a party and, above all, of reading.

You mentioned in the essay that accompanied your entry that you have been a collector of books and ephemera from a young age. What were some of your early collecting interests?

My favorite anecdote to tell when discussing my collecting is that in fourth grade (year 5 in the UK system), we were asked to bring in a collection for show and tell. Most of my peers brought in what you would expect of 9-year-olds in 2002—Beanie Babies, baseball cards, or rocks—while I was the only student to bring in a book collection. I still remember giving my presentation and being incredibly proud that I had over one hundred books. So, I guess the bibliophilia was innate!

Beyond books, I’ve also collected stickers, pins (badges), patches, and assorted ephemera since I was a kid. For whatever reason, I always had the impulse to archive my material life, so I have notes passed to me by school friends, bookmarks, postcards, brochures from trips taken, even interesting foreign packaging that I squirreled away. Someday, I hope to scan it all and have a photo book printed up—it’s such a fun story of my youth as told in ephemera.

Is your approach towards collecting more completist or curatorial? And what do you think the collecting urge is all about?

I would say my collecting leans both ways. My party-planning collection is actually just part of a broader collection that encompasses over eight-hundred books and pieces of ephemera. There are five main sub-collections (cookery and home economics, liquor advertising, gelatine advertising, erotica, and party planning), with a fair amount of overlap between the categories (e.g. “The Jell-O Girl Entertains”).

Looking at the collection writ large, I would say it tends toward the curatorial. I have been interrogating my collecting interests a lot lately, thinking about the coherence of the different pieces taken together, and I’ve come to see it as an attempt to understand how the female gaze and feminine desire are rendered visible through the material text. And this is not to say in any exclusionary way; the broadside of a performance by Bambi Lake in San Francisco in the 90s or the August 1962 issue of Confidential magazine in which Coccinelle reflects upon her transition both materially represent what it means to be a woman in print, to design printed materials about women, for women, for trans women and cis women alike.

In this way, it’s very much curatorial, as that interest in feminine desire reflects back upon my own collecting practice and positionality as a female collector. So much of the literature about collecting is male-focused and uses highly gendered (and sexualized) metaphors, so it’s been interesting to think about what it means to be a woman who looks upon texts avariciously, with an intent to possess. I could never collect a “complete” textual record of the feminine gaze, but I can curate a collection that reflects my own tastes (and thus my own feminine gaze), as well as the trends in women-oriented, popular bibliographic design in the twentieth century.

My party-planning collecting specifically, however, is much more completist. As I mentioned earlier, I found while doing my master’s research that there were no major collections of these materials held at research institutions. I quickly decided that I would try to create as complete an archive of twentieth-century American party planning books and ephemera as possible.

Looking to the future, I hope to donate my collection to my alma mater, Scripps College, a women’s college in Southern California. Putting my collection in conversation with other women’s history materials, while also making it available to students in the milieu where I first fell in love with rare books and special collections, seems the most meaningful end point for my collecting. And so, with an eye towards this becoming a research collection, I am always aiming for as complete a historical record as possible.

Your collection highlights midcentury social and sexual conventions through the lens of party planning. Can you tell us what the collection has taught you about this period?

Because most of the texts in my collection were published as advertisements—for food products, cigarettes, liquor, tableware—they are artifacts of corporate understandings of consumers, rather than records of the actual tastes and parties of the readers at midcentury. In this way, it doesn’t teach me a whole lot about what consumers were actually doing, thinking, feeling about their party giving, apart from the occasional manuscript inscription indicating a recipe that worked (or didn’t) or perhaps a starred table setting in a catalog.

Taking this top-down perspective, I’ve learned a great deal about how dominant culture was transmitted via these seemingly innocuous printed ephemera. The best example would be my small sub-collection of Hawaiian party materials. As the 50th state to join the US in 1959, there was a lot of fascination with Hawaii and Hawaiian culture during the midcentury period. This was fuelled in part by the United States’ interest in assimilating Hawaii into American culture and compounded by companies’ desire to cash in on the hype. One such booklet in my collection, “How You Can Give Hawaiian Parties,” was published by the Hawaiian Pineapple Company, now known as Dole Food Company, a key player in the annexation of Hawaii. The booklet is full of watered-down luau traditions and Americanized Hawaiian dishes. In this way, the Hawaiian party digests the traditions of the Indigenous Hawaiians into a vehicle for soft power and justification for their colonization.

On a lighter note, my collection has really driven home to me just how much everyone smoked in this period! Table settings will include ashtrays and cigarette cups, etiquette books will remind the hostess that it’s her job to periodically empty all the ashtrays during the party. It’s something I did know, but didn’t fully grasp until I started collecting...

The Book Collecting Prize came with £500 to help expand your collection. Have you already put this money to use, and if so, what have you acquired?

Honestly, I spent most of the money even before it arrived! It’s been a dream moving to Wisconsin; I’ve been able to source some really incredible ephemera, in particular. It’s now gotten to the point where I’ve had to start limiting my trips to local antique malls...

One recent favorite is “Pizza Party Ideas,” an advertising booklet for “Chef Boy-Ar-Dee Pizza” from the 1950s. My mom is Italian-American and I’ve long been interested in the introduction of Italian food to Americans. “Chef Boyardee” was Ettore Boiardi, an Italian immigrant to the US in the early twentieth century, who was a major force in popularizing Italian food to Americans. And, indeed, when I checked out at the antique mall, the ladies working at the register told me that the first time they had ever eaten pizza it was that exact “Chef Boy-Ar-Dee Pizza.”

I also finally purchased a Tupperware party planning book—the fifth edition of Know How! The Guide to Making Money with Tupperware. Tupperware parties were such an important part of midcentury culture and have a fascinating, gendered history. The “party plan” sales concept was invented by a woman, Brownie Wise, who worked for the Tupperware Company in the 1950s. Her idea, however, was essentially stolen by the Tupperware founder, Earl Tupper, who became jealous that she was (rightly) credited with the company’s success and fired her, going on to expunge any trace of her from the company’s history. He went so far as to take remaining copies of the autobiography she had written about her success and bury them in a pit near the Tupperware headquarters! Many of the party planning books are connected to entrepreneurial women, who took the limited roles available to them at the time and translated them into major success—Amy Vanderbilt, Laura Scudder, Virginia Stanton, and Brownie Wise all come to mind.