ABA News

My Own Two Hands: An Interview with Emma Treleaven

Emma Treleaven on her 2023 National Book Collecting Prize winning collection, which highlights the often-hidden talents of generations of domestic women, and preserves the precious ephemeral records of their work for future makers.

Congratulations on winning the National Book Collecting Prize! Your collection 'My Own Two Hands' is an enlightening record of dressmaking and textiles before 1975, including materials often overlooked by dealers and collectors. What have been your main sources for acquiring items for this collection?

Thank you very much! I’m thrilled the ABA judges also appreciate the material I am so passionate about.

My collection has grown in a slightly odd way — more often than not my acquisitions find me! Most of what I collect was very commonplace in most homes in the 20th century, so I often get people gifting me books and ephemera that belonged to their grandparents or older friends or elderly neighbours. Even my volunteers at work sometimes bring me wonderful items! I love it when this happens because I get to find out a bit about the person who owned and used them originally, which doesn’t usually happen when you purchase something from a shop, fair, or online. Most people tell me they don’t have an interest themselves, but whatever they are offering seemed too important to throw away somehow, so they are usually really happy the material has found a home with me.

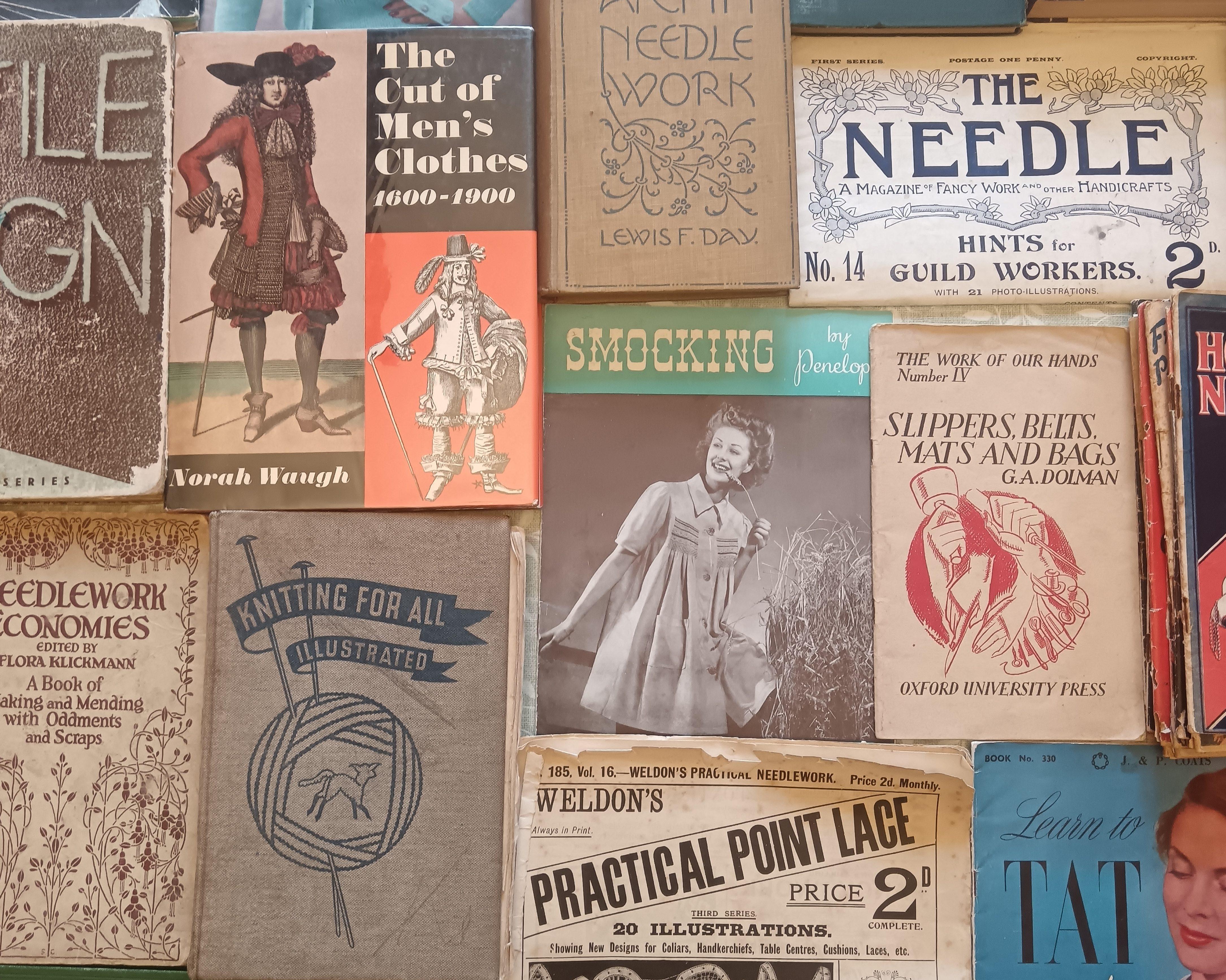

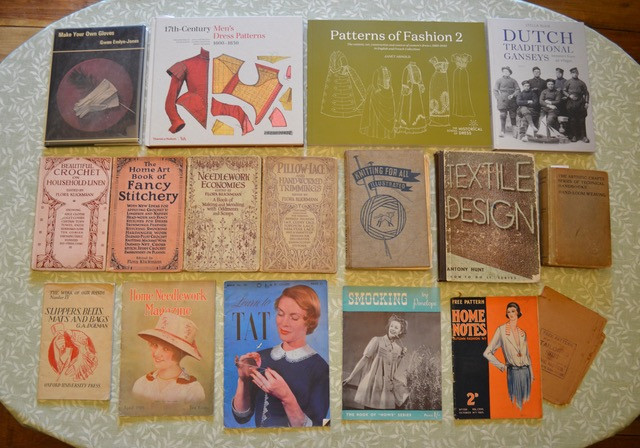

Otherwise, I often have decent luck in charity shops, again because what I’m looking for was fairly common a generation or two ago, but I do find exciting things at book and ephemera fairs from time to time too. Sometimes I will go searching for something specific online, but mostly I stumble across enough additions to my collection without actively looking to keep the collector in me happy.

Do you have a favourite item from the collection?

I wouldn’t say I have a favourite, but I do have things that excite me more than others at times, or books I use more often than others.

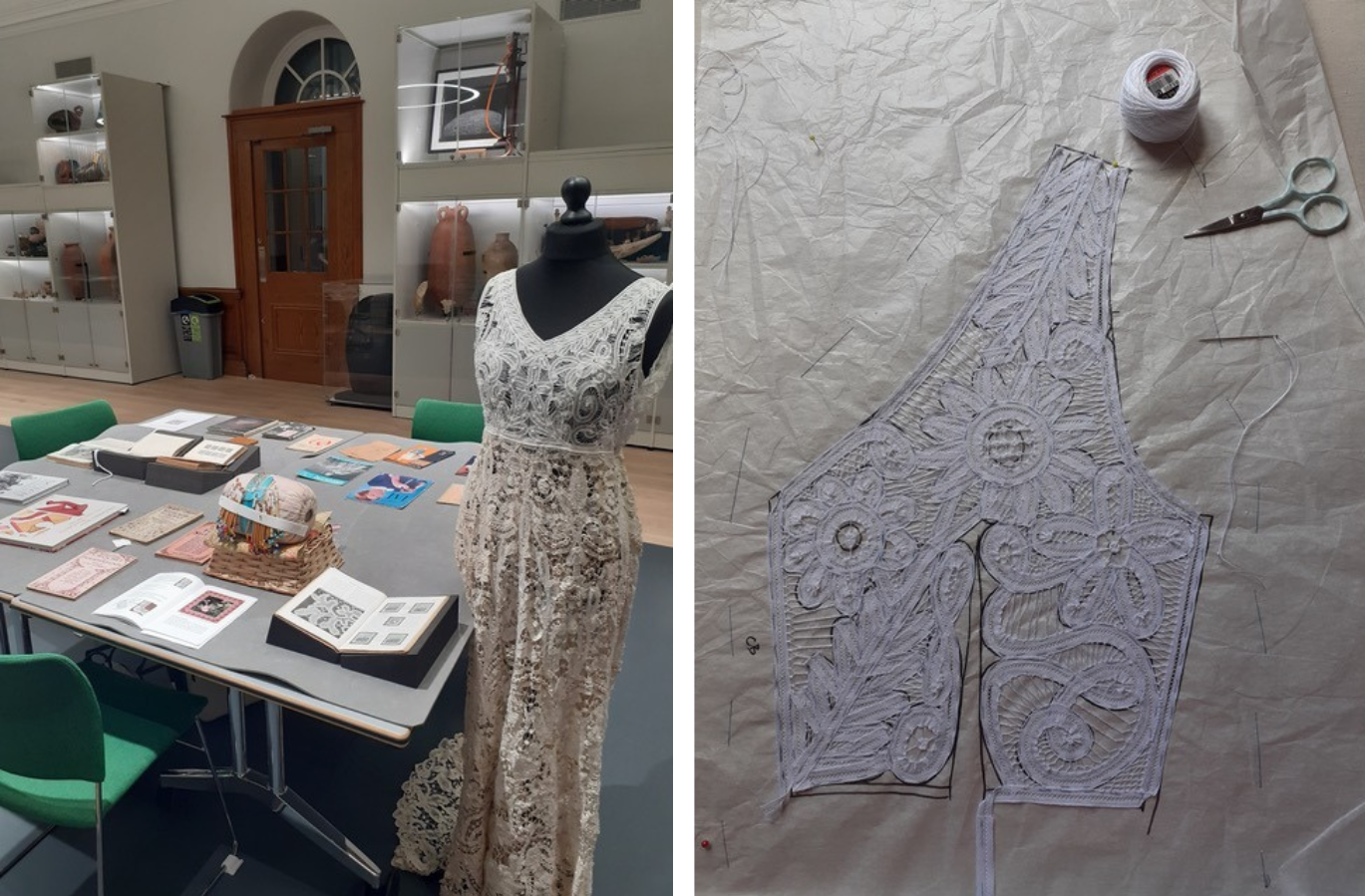

I tend to go down rabbit holes when it comes to my making. When I get going on something, like silk flower making or 1930s pattern cutting, I get all the materials I have in my collection about that one idea or method or era out for inspiration and to help me learn. My wedding dress is a good example of this; I made the bodice to match an original skirt from about 1912, which is made from a type of needle lace called Battenburg lace. My needle lace pamphlets and books were my constant companions for about 4 months while I made my bodice!

The ones I flip through the most often are probably my needlework compendiums, like my ‘Weldon’s Encyclopaedia of Needlework’. These compendiums usually contain everything from art deco rug making to hideous crochet doilies, to really chic knit hats, to fluffy baby jumpers, so they give an interesting view into the range of skills of domestic makers of the early-mid 20th century, as well as being charming, hilarious, and inspiring in equal measure.

The collection preserves material that was created for a largely female, domestic audience, often printed on perishable or fragile materials. How has the ephemeral nature of the collection influenced your feelings about being a collector?

It makes me feel more like a caretaker of knowledge, rather than just a collector. I collect these things for me, but ultimately I’m scared that if no one does, we will lose all of this beautiful knowledge and technique that was so important to women in the past.

The ephemeral nature of these materials is part of why I started collecting them in the first place. When I first started trying to figure out how to make more niche historic dress and textiles, it was often only the extremely beat up, slightly falling apart library books shoved on a bottom shelf that could answer my questions, which I found really sad and frustrating. If these materials were on their last legs now, what was going to answer the same nerdy questions I had in 50 or 100 years time? And then once I started thinking about that, it just ballooned really, and I went right down the collecting rabbit hole.

One of the benefits of caring about the knowledge in these materials is that I can collect quite widely, which in turn gives me more options of things to make in the future. I might not want to make a waistcoat lined with old leather gloves at the moment, but at least because I’ve collected the how and why someone did during WWI, myself and subsequent others have the option to!

This collection is very special in that it's a working collection, one that you use for research and making. Do you feel you've gained an insight into the lives of the women for whom these materials were originally created, through your active use of the same resources?

Absolutely! Most of my collection is about as far from ‘gods copy’ as you can get. I love seeing the use, the annotations — the signs that another person used what I’m holding to learn something or express their creativity in the past.

It’s especially fun when you get fitting or alteration notes. I love seeing how women customised projects and patterns for themselves, whether it's adding more room in the bust or using green yarn instead of blue, it all makes it more personal. Sometimes I’m even lucky enough to get the name of a past owner, which really brings the people to life for me.

You can learn a lot about how skilled these women were by giving the projects in my collection a go. Even the simplest things require a high level of manual dexterity, precision, and understanding of materials that most people today just don’t have. The base knowledge and skill level of a typical woman in a ‘domestic’ setting pre 1975 is so much higher than written history would lead us to believe, which can really be seen and felt throughout these materials. The more I use these materials the more respect I have for the women makers who came before me.

One of your aims with this collection is to preserve material and techniques that might otherwise be lost. Do you have an endgame in mind in terms of donating it to an institution, or will it continue to grow exponentially?

I would love to find an institution to donate it to eventually, but probably not until I’m old with arthritic hands and poor eyesight! Until then I plan on using it all to the best of my ability.

I know this is a common issue, especially as I work in museum collections, but I would really want my collection to be used in the same way I use it, not just have it sitting on a shelf gathering dust. I want it to remain a working collection for as long as possible, so I guess I would try to find an institution that could use it in teaching, or would have students that are likely to be interested makers.

Another reason I probably will keep growing it till I’m old and grey is wherever I donate it to, I would want to give them enough money to catalogue and house it all. I know all too well how short staffed and short of money libraries, archives, and museums are, and what a backlog large collections can cause in making material available. If I want to make sure my collection is as useful as possible, I feel like the only fair thing to do would be to accompany my donation with some funding alongside it!

Is there a favourite fact about dressmaking history, technique, or piece of trivia that you have learned as a result of this collection?

I don’t really have a favourite fact or technique, but I do think parts of my collection offer surprising bits of worldly wisdom or a good laugh.

Quite a few items, particularly those published during WWI and WWII, encourage mending, buying the best quality materials you can afford, and boycotting fast fashion. These are concepts that are very relevant in today’s world, but I think most people assume they are modern reactions to the current climate crisis, not something that has been worrying women makers for hundreds of years. The designer Vivienne Westwood said ‘buy less, choose well, make it last’, which is a motto many of the authors of the materials in my collection would heartily agree with.

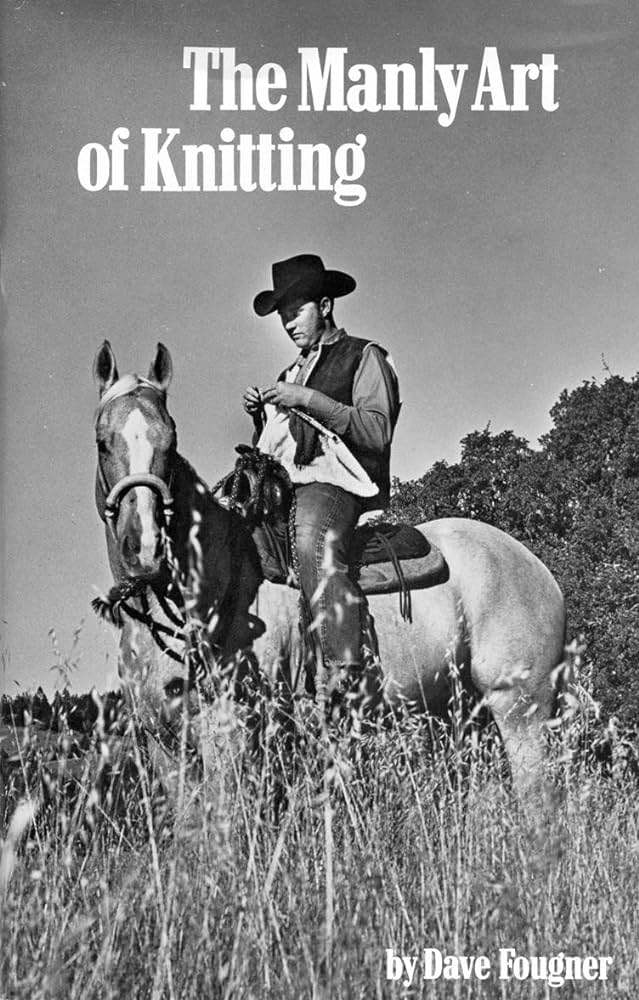

One of the oddest books in my collection is ‘The Manly Art of Knitting’, published in 1972, which features a cowboy on a horse engrossed in his knitting on the cover. The ‘history’ section at the beginning states that as recently as the late 19th century it was common for men to knit, a fact which I have never seen any evidence of, but hey, if it encouraged more 1970s men/boys/cowboys to pick up some needles I won’t complain!

The Book Collecting Prize came with £500 to help expand your collection. Do you have plans for how to spend this money yet?

I have a few ideas! I really didn’t expect to win so I don’t have any firm plans dreamed up yet, but I would like to spend some of it on things that I’ve wanted for ages but not had the excuse to purchase yet, such as a collected volume of the Dryad Handicrafts leaflets from the mid- 20th century. Like needlework compendiums, these leaflets cover a huge range of subjects, from fabric printing to shoemaking, and have really interesting instructions.

I recently ran across a book called How to Become a ‘Professional’ Amateur Dressmaker from 1962 that I would love to have a copy of, as I think it promotes a level of skill that many dressmakers, including myself, try very hard to achieve despite our ‘amateur’ status.

But the main thing I have in mind is trying to acquire more manuscript material, such as sample books from women or girls learning how to sew. I recently acquired one of these from 1927 and it’s so personal, I feel really lucky to have it. I certainly hope she got an A because her sewing and penmanship is exquisite, much better than mine when I was making a similar booklet in my high school fashion class! Most manuscript material I see, like 18th century lace making pattern books, is always way out of my price range, but this prize should hopefully help me add some really lovely more recent manuscripts to my collection.